Chapter 3: It's Africa Hot

There is nothing "nice" about Camp Doha - about 20 miles outside of Kuwait City.

It is hot. As Eugene Jerome said about boot camp in Biloxi, Mississippi, "It's Africa Hot."

The day we were there it was 122°.

It is so hot in Camp Doha, that many soldiers routinely carry a pair of gloves on the chance they will have to touch something metal, like a truck, which has been annealing in the sun.

We left the luxury of the Marriott Hotel at about 8 am in a mini-bus. The ride out to the base was about a half hour.

When we got there we were met by an official of the US Embassy - a young man who had been with us the previous day when we had met with Ambassador Robert Jones - so he was working not only on the weekend, but on a holiday as well. I wonder if Foreign Service Officers get double time for that?

We drove up to the guard shack and were told to get out of the bus. We did and were met by several security guards who are civilian contract employees.

A public affairs officer from the base, whom I described in Mullings as having a ranger patch on his shoulder and an airborne badge on his chest was to be our guide.

That's the ranger patch above the Third Army insignia. The Third Army was, as we remember from our vast movie-going experience, Patton's unit during the race across Europe in World War II.

These soldiers did nothing but enhance Third Army's reputation and image as one of the finest fighting forces in history.

Anyway, we gave our names, got back on the bus, drove through the gate and were immediately told to turn the bus around, park it on the OTHER side of the guard shack, come through the magnetometers, and surrender our passports before we were going to be allowed on the base.

The PA said this was going to be the safest, most closely inspected bus in the history of Camp Doha.

The whole process took about 40 minutes while they examined our papers, checked our names off lists, and allowed us to add the name of our Kuwaiti handler who, had not been put on the list by the US Embassy.

While we were waiting we were asked if anyone had taken photos of the guard shack or the surrounding area.

I had. I was asked to delete the photo. I did.

Having been in the Army National Guard, I was not upset, or put off by all this. If you've been in the military you come to understand two things: First, you will NEVER forget your service number. Nowadays it is your social security number. Back in my day it was NG21801329. I haven't had to use that number since the late 60's. I've never forgotten it.

The second thing you come to understand is the military is not illogical. It is A-logical. There is no logic whatever to what happens or doesn't happen.

One of my best friends in college - and still a good friend to this day - was drafted after he graduated and found himself in a line heading into a building to be assigned after training. Being in a line in the military is something less than a rare occurrence.

There was a parallel line going into a different door right next to his line. He happened to ask someone coming of the door into which the other line was going where he had been assigned.

The guy said, "Germany," so my friend simply walked two steps to his left (or right) and got into the other line.

He went to Germany instead of Vietnam.

When I was in the Army I did basic training at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. I vowed, afterward, I would never step foot in North Carolina again. I lied, of course, but I have never stepped foot on Fort Bragg again.

While the temps at Bragg were nothing like Camp Doha, I got there in June and spent all of that month, and all of July doing my 8 weeks of basic.

We were housed in a World War II-style wooden 40 man barracks: Twenty soldiers upstairs and twenty down.

There were two rows of double-decker bunkbeds placed end-to-end, one along each side of the barracks with a big open space between them.

If you've seen Full Metal Jacket, you've seen my barracks. And the barracks of about 10 million other guys.

A standard basic training squad is 10 men, a squad leader and nine soldiers. There are four squads in a

platoon and four platoons in a company. 160 men.

My platoon was made up of about half White guys from North Carolina and Georgia; and half Black guys from Washington, DC and Philadelphia.

This, remember, was the 60's and the notion of ignoring Race had not yet become part of the culture of either of these two groups.

Like every war movie you've ever seen, when we first got to the basic training area there were Sergeant in Smokey-the-Bear hats screaming at us to move, Move, MOVE! into the barracks.

We had heavy duffle bags with our clothing and equipment - all courtesy of Uncle Sam. I weighed about 128 when I went into the Army. I came out at about 140.

My duffle bag weighed about a third of what I weighed.

We ran into the barracks and took the first empty bunk bed. As I was a little slower than everyone else, I ended up on the second floor.

Both floors were mixed race.

That lasted until the first night when all the Black guys migrated upstairs, trading places with all the White guys who were now on the first floor.

Because I had about 17 minutes of National Guard training before I had reported for active duty I was made a squad leader of one of the upstairs squads.

It was me and 19 black guys.

The upstairs crowd and the downstairs crowd didn't get along all that well. In fact they fought just about constantly.

I knew when a fight was about to start because the biggest guy in the platoon - who happened to be in my squad - would come over and stand next to me. I suppose this is a sign of good leadership when the other nine guys send their biggest guy, not against the enemy, but to make sure I didn't get hurt.

We had the usual scrapes and gunshot wounds. Yes, that's true. One guy actually shot another. Happily our guys were not only goofballs, they were terrible shots so the shooter barely grazed the shootee.

They were both from my platoon, but neither was from my squad.

I lost a squad member briefly when one of the White guys from downstairs took a swing at him with what we called an "entrenching tool" (a shovel) and caught him in the neck with the edge of the blade.

My guy was only gone about a day while they sewed him up at the base hospital, made certain he wasn't going to come back to me as a Black version of "Nearly Headless Nick," and marked him ready for duty.

Everyone who has ever been in basic training will tell you this: The little nicks, scraps, bumps and bruises go unnoticed. A slash to the neck … that gets noticed.

So, having had six months of no-kidding-around active duty, I felt perfectly at home at Camp Doha.

At least I felt perfectly at home in the air-conditioned mini-bus at Camp Doha.

Camp Doha is a depot. About 8,000-10,000 soldiers come through there every day to repair equipment, to make incoming equipment ready for Iraq, or to make equipment which is being shipped home ready for the journey.

Here is an example:

The chalk sign says, "Proud Supporter of the 3rd ID."

Rolling stock and tracked vehicles are washed and repaired here:

And helicopters are repaired here, as well.

The Captain who was our tour guide told us that he was, that afternoon, moving from a bunk-bed barracks into a trailer which he would share with one other officer.

In the military, officers of like rank are housed together: Second and First Lieutenants with other junior officers. Captains are together; as are field grade officers (Majors, Lt. Colonels and Colonels). General Officers ascend and descend from heaven each day and need no housing.

This is not because Colonels don't want to association with Second Lieutenants. It's so the Second Lieutenants don't have to spend all their time saluting and worrying about being around higher-ranking officers all the time.

There actually is some logic to all this.

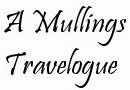

Anyway, here is a photo of the Captain's new digs:

As were were driving around the base, we saw New Jersey Barriers which had been decorated by the troops. This was an example:

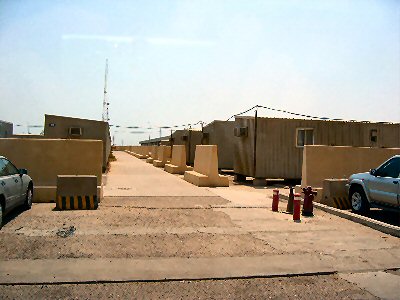

No matter where you go in the world, if you give American soldiers a big enough space, this will happen:

120 degrees. Hah.

We went to the PX (which stands for Post Exchange). Because it was a holiday, most of the soldiers were in civilian clothes. But they all looked like they were trying out for a recruiting poster.

I had to purchase some tee shirts and toiletries (to replace the ones which Air France stole from me) as well as a new flag for Mullings Central.

I was standing in line behind a group of soldiers who had just rotated out of Iraq. This was approximately the conversation:

At this point they heard me laughing behind them. I'm OLD enough to be a General and they stood up straight as they apologized to me, SIR.

I told them I was a civilian, enjoying a conversation I hadn't heard since my days at Fort Bragg.

The first young man went off to effing aisle three to buy some effing sunscreen while the second kid held his effing place in line.

I loved it.

Back outside we were reminded that we were still in a place which could become dangerous:

And overhead there were roving patrols:

As our bus was leaving the base, we stopped at the guard shack while our passports were recovered from the security people.

As we were waiting we heard the sirens of a convoy coming toward us. Unfortunately, it all happened too quickly to get a picture, but it was a convoy - complete with security fore and aft - carrying Arnold Schwarzenegger arriving to entertain the troops.

Arnold had been to Baghdad, and was now going to the three bases around Kuwait. That night they were showing his new movie, "Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines."

The English Language papers the next day had the soldiers giving Arnold high marks for coming to see them.

I suggested he had a motorcade as befits the next Governor of California.

Hearty laughs all around.

As we started up again, the Captain told us to look over at the smokestacks above the base power plant.

As is the case with soldiers everywhere, black humor found its way to Camp Doha.

The soldiers had named them the "Scud Goalposts."

Next: Votin' Day.

Click here to return to the Secret Decoder Ring page

Kuwait Here. I'll Be Right Back

Soldier 1: I couldn't find the effing sunscreen.

Soldier 2: It's over in effing aisle three.

Soldier 1: Hold my effing spot so I can effing go over and get some, will you?

Soldier 2: Just don't take too effing long, I'm not your effing slave.